European parliamentarians have voted overwhelmingly to reject the reduction of textile tariffs for Uzbekistan until the International Labor Organization (ILO) is given access to the country to examine extensive reports of forced child labor.

Members of the European Parliament voted 603-8 to send the textile protocol to the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) between the EU and Uzbekistan back to the European Commission.

Members of the European Parliament voted 603-8 to send the textile protocol to the Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) between the EU and Uzbekistan back to the European Commission.

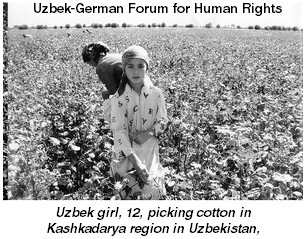

In the text of the resolution, the European parliamentarians “[s]trongly condemn the use of forced child labour in Uzbekistan” and “[u]rge the Uzbek President Islam Karimov to allow an ILO monitoring mission into the country to address the issue of forced child labour practice.” The MEPs further specify support for the ILO’s request for “a high-level tripartite observer mission that would have full freedom of movement and timely access to all locations and relevant parties, including in the cotton fields, in order to assess the implementation of the ILO Convention.”

In October, the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament voted unanimously against the inclusion of the textiles protocol in the PCA. The vote prevented a lowering of tariffs on EU imports of Uzbek cotton, which make up at least 25 percent of Uzbekistan’s exports. Then in November, the European Parliament’s International Trade Committee also refused to give consent to the trade agreement unless the ILO was allowed to enter Uzbekistan to investigate conditions and confirm that the problem of child labour was being concretely tackled. The London-based Anti-Slavery International spent a year gathering 13,072 signatures through change.org and other campaign sites, persuading pop singer Ricky Martin to endorse the effort, and ethical fashion and consumer bloggers to link to their petition. The campaigners hand-delivered the package of signatures to MEP Catherine Bearder, a Liberal Democrat, on December 6.

The vote signifies a new-found resoluteness on the part of European legislators to fight forced child labor and trafficking by attacking corporate profits. Without the tariff break, European cotton traders would presumably be discouraged from importing more expensive cotton — which they had purchased in the first place because it was cheaper on the world market. Some 60 companies and a trade association pledged not to source their cotton in Uzbekistan this year. Yet the de-facto boycott of Uzbek cotton seemed to do little to dent business at the annual Tashkent International Cotton Fair, where record sales were made (although in less volume). No Western trader appeared to be buying the cotton, and in their absence, companies from Russia, China, India and elsewhere were picking up the slack.