Nigeria’s textile and garment sector has been on a decadeslong decline. Image: Monika Skolimowska/dpa/picture alliance

Nigeria’s Textile Industry Faces Crisis Amidst Competition from Chinese Imports, Calls for Urgent Revitalization

Chinese Imports Threaten Nigeria’s Textile Industry

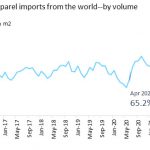

Lagos, Nigeria – Once a thriving pillar of Nigeria’s economy, the country’s textile industry now stands at a crossroads, grappling with a dramatic decline fueled by an influx of cheap imports, particularly from China. In its heyday during the 1990s, Nigeria’s textile sector was a vibrant force, employing hundreds of thousands of workers and anchoring industrial cities such as Kaduna, Kano, Lagos, and Onitsha. This sector not only met domestic demand but also supplied high-quality fabrics to international markets, creating a robust ecosystem that supported local cotton farming and industrial growth.

Today, this once-flourishing industry is a shadow of its former self, with fewer than four textile factories still operational. The decline is largely attributed to the price disparity between Nigerian-made textiles and the low-cost fabrics flooding the market from China. Chinese manufacturers enjoy the advantage of a fully integrated supply chain, domestically producing everything from raw materials to synthetic fibers and machinery. This efficiency enables them to undercut prices, leaving Nigerian manufacturers struggling to compete. In contrast, Nigeria’s textile producers are burdened with importing essential materials like dyes, chemicals, and synthetic fibers, further driving up costs.

Anibe Achimugu, President of the National Cotton Association of Nigeria, emphasizes that China’s ability to locally source raw materials provides a critical advantage, allowing for significantly lower production costs. Coupled with the depreciation of the naira following President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s 2023 decision to float the currency, the cost of importing materials and spare parts has soared, intensifying the challenges faced by Nigerian manufacturers.

Hamma Ali Kwajaffa, head of the Nigerian Textile Manufacturers Association, paints a grim picture of the industry’s struggles. Imported textiles not only mimic Nigerian designs but are often crafted from inferior polyester materials, which lack the durability and quality of locally made cotton fabrics. These counterfeit imports are sometimes illegally labeled as “Made in Nigeria,” eroding trust in genuine local products. “The counterfeit fabrics fade quickly and don’t last. When consumers mistakenly associate these poor-quality textiles with Nigerian manufacturers, it damages the reputation of our industry,” Kwajaffa explains.

Government interventions aimed at rescuing the industry have yet to yield tangible results. The Textile Development Fund Levy, introduced in 1997 to impose a 10% tax on imported textiles and fund local production, has been ineffective. According to Kwajaffa, manufacturers have not received any financial support from this initiative. The resulting lack of investment has led to mass closures of textile mills, with the number of operational factories plummeting from over 150 in the 1990s to the current count of fewer than four. This downturn has also devastated cotton farming, with the 2024-25 season described as one of the worst in living memory.

The crisis extends beyond Nigeria’s borders, as the country has withdrawn from the International Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) due to an inability to pay membership dues. This organization, which provides crucial global market data and research, could have supported Nigeria’s efforts to revive its textile sector. However, financial constraints have made it impossible for the nation to maintain its participation.

In addition to these challenges, Nigeria’s unreliable electricity supply has compounded production costs. Manufacturers are often forced to rely on diesel generators, further inflating expenses and making it even harder to compete with countries like China, where stable power supplies contribute to lower production costs.

Despite these obstacles, there are glimmers of hope. In 2024, the Nigerian government secured a $3.5 billion loan from the African Export-Import Bank to revitalize the textile industry. However, industry leaders remain cautious, noting that the disbursement of such funds often faces delays. Kwajaffa compares the wait for these funds to “waiting for Godot,” expressing frustration over the lack of transparency and involvement of stakeholders from the textile and garment sectors in discussions about the loan’s allocation.

To save the industry from total collapse, stakeholders are calling for comprehensive reforms. These include ensuring that financial support reaches manufacturers, addressing the prevalence of counterfeits, and creating a conducive environment for local production by stabilizing power supplies and reducing reliance on costly imports. Industry experts stress that leveraging Nigeria’s domestic cotton production could play a pivotal role in revitalizing the sector, provided that government policies and investments align with the needs of producers.

Once a source of national pride and economic strength, Nigeria’s textile industry now faces an existential crisis. However, with coordinated efforts from the government, industry stakeholders, and international partners, there remains a pathway to recovery. Reviving this industry is not just an economic imperative; it is a chance to restore livelihoods and reestablish Nigeria’s position as a leader in the global textile market.