Mark Anner, Ph.D.,

Director, Center for Global Workers’ Rights in Association with the Worker Rights Consortium

A Research Brief by the Center for Global Worers´Rights (CGWR) draws from responses from an online survey of Bangladesh employers, administered between March 21 and March 25, 2020, to document these trends. It reveals the devastating impact order cancellations have had on businesses and on workers. Crucially, it illustrates the extreme fragility of a system based on decades of buyers squeezing down on prices paid to suppliers: factory closures, unpaid workers with no savings to survive the hard times ahead, and a government with such a low tax revenue that it has very limited ability to provide meaningful support to workers and the industry.

Executive Summary

The global Covid-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on global garment supply chains, and the situation will get far worse before it gets better. As clothing outlets have been shut by lockdowns in developed market economies, sinking demand for apparel, brands and retailers have moved quickly to cancel or postpone production orders – refusing, in many cases, to pay for clothing their supplier factories have already produced. The result has been the partial or complete shutdown of thousands of factories in producing countries. As a result, millions of factory workers have been sent home, often without legally-mandated pay or severance.

This Research Brief draws from responses from an online survey of Bangladesh employers, administered between March 21 and March 25, 2020, to document these trends. It reveals the devastating impact order cancellations have had on businesses and on workers. Crucially, it illustrates the extreme fragility of a system based on decades of buyers squeezing down on prices paid to suppliers: factory closures, unpaid workers with no savings to survive the hard times ahead, and a government with such a low tax revenue that it has very limited ability to provide meaningful support to workers and the industry.

- Since the coronavirus pandemic took hold, more than half of Bangladesh suppliers have had the bulk of their in-process, or already completed, production canceled (45.8% of suppliers report that ‘a lot’ to ‘most’ of their nearly completed or entirely completed orders have been canceled by their buyers; 5.9% had all of these orders canceled). This is despite the fact that buyers have a contractual obligation to pay for these orders. But many are making dubious use of general force majeure clauses to justify their violations of the terms of the contract.

- When orders were canceled, 72.1% of buyers refused to pay for raw materials (fabric, etc.) already purchased by the supplier, and 91.3% of buyers refused to pay for the cut-make-trim cost (production cost) of the supplier. As a result of order cancellations and lack of payment, 58% of factories surveyed report having to shutdown most or all of their operations.

- More than one million garment workers in Bangladesh already have been fired or furloughed (temporarily suspended from work) as a result of order cancellations and the failure of buyers to pay for these cancellations. Suppliers in the survey reported that 98.1% of buyers refused to contribute to the cost of paying the partial wages to furloughed workers that the law requires. 72.4% of furloughed workers were sent home without pay. 97.3% of buyers refused to contribute to severance pay expenses of dismissed workers, also a legal entitlement in Bangladesh. 80.4% of dismissed workers were sent home without their severance pay. This is despite the fact that many brands have “responsible exit” policies, in which they commit to support factories in mitigating potential adverse impacts to workers should they decide to exit.

- The survey findings presented in this report depict the most comprehensive evidence to date on the depth of the crisis in Bangladesh. The essential dynamics presented here are evident in garment exporting countries worldwide.

Recommendations

All parties are feeling the extreme burden caused by Covid-19. However, not all parties are equally situated to find the liquidity needed to cover their expenses. As shops, outlets, and malls are ordered shut, retailers and brands are taking an enormous hit to their bottom line and cash reserves. However, the hit on supplier factories, who generally operate on paper-thin margins and have far less access to capital than their customers, is that much more extreme. And the burden on workers – who very rarely earn enough to accumulate any savings and who still need to put food on the table and possibly cover unforeseen health expenses – is enormous.

- It is incumbent on the parties with the greatest ability to procure loans and benefit from government bailouts to share those benefits down the supply chains. In this regard, we call upon all buyers to respect the terms of their purchasing contracts and pay suppliers for orders already in production or completed.

- Suppliers, for their part, must ensure that payments received from these buyers are used to cover all legally mandated wages and benefits, including severance payments to dismissed workers.

- The government of Bangladesh must continue to mobilize all the resources at its disposal to subsidize suppliers and provide wage support to all workers during the crisis.

- Going forward, buyers should learn from this crisis to revise purchasing practices to ensure proper social and environmental sustainability. These changes include order stability that allows for proper planning, timely payments of orders, and full respect for workers’ rights. It also includes a costing model that covers all the costs of social compliance: living wages, benefits, severance pay, building safety, etc. One way to cover some of these expenses is an additional charge levied on freight on board (FOB) prices.

- Given present realities, adequate protection for the vast numbers of garment workers affected by the crisis, in Bangladesh and across the global supply chain, will require the mobilization of international financial resources. The cost of maintaining income for the world’s garment workers represents a small fraction of the trillions in financial stimulus and rescue now being brought to bear on behalf of businesses and workers in wealthy countries.

Apart from the tremendous human tragedy left in its wake, the coronavirus pandemic will have profound economic repercussions for workers everywhere. The effects of the global economy’s collapse will worsen before they ameliorate and will continue to be felt for years to come. The International Labour Organization predicts that 25 million jobs will be lost worldwide as a result of Covid-19.2 Workers in global supply chains are particularly vulnerable to termination and economic destitution.

As governments in wealthier countries order lockdowns to control the pandemic, demand for apparel is plummeting, leading many brands and retailers to halt production. As a result, factories around the world are shuttering, rendering millions of garment workers in Bangladesh and beyond jobless. These are workers who, prior to their termination, were making extremely inadequate wages and for whom saving up for a safety net was never an option.

While anecdotal accounts in the media have already begun to paint a disheartening picture of the effects of Covid-19 on the global garment workforce, this research brief provides strong empirical evidence exposing the breadth and depth of the problem in Bangladesh’ s garment sector.

The next section discusses the methods employed in this study. This is followed by a section outlining the three phases of the Covid-19 crisis for the garment sector in Bangladesh, after which the profound impact of the crisis upon garment workers is examined. The government’ s response to Covid-19 in Bangladesh follows, before concluding with a set of recommendations.

Methods and Data

This report draws on a survey of Bangladesh suppliers conducted online between March 21 and March 25, 2020. There are approximately 2,000 suppliers in Bangladesh and 4,000 factories (many suppliers own multiple factories). Of these, 316 suppliers completed the survey. This puts the sample size within the approximate confines of a 95% confidence level and a 5% confidence interval.

Of the respondents, 15 are owners of small factories (250 or fewer workers), 104 are owners with medium sized factories (between 251 and 750 workers), and 197 have 751 or more workers. Most of the buyers of these suppliers (67.7%) are European; 15.8% are American, 4.8% are Asian, and the remainder are “other” or a mix of American, European, and Asian firms.

Three Phases of the Crisis

The current crisis facing the garment sector in Bangladesh developed in three phases. First, there was the crisis of ‘raw materials’ procurement. Second, there was the crisis of buyer late payments. Third, there has been the crisis of buyer cancellations of in-process orders. The culmination of these three phases has been devastating on businesses and over 1 million workers. The survey covers these three phases.

Crisis Phase One: Raw Materials

On December 31, 2019, the government of China alerted the World Health Organization (WHO) to a health emergency in Wuhan City in the Hubei province. Just over three weeks later, the government placed Wuhan’s 11 million inhabitants on lockdown. Other cities in the province followed suit soon afterwards. For garment global supply chains, this impacted not only Chinese exports of final products, but it dramatically impacted Chinese raw materials (notably fabric) needed by exporters elsewhere, from Bangladesh and Cambodia to Honduras.

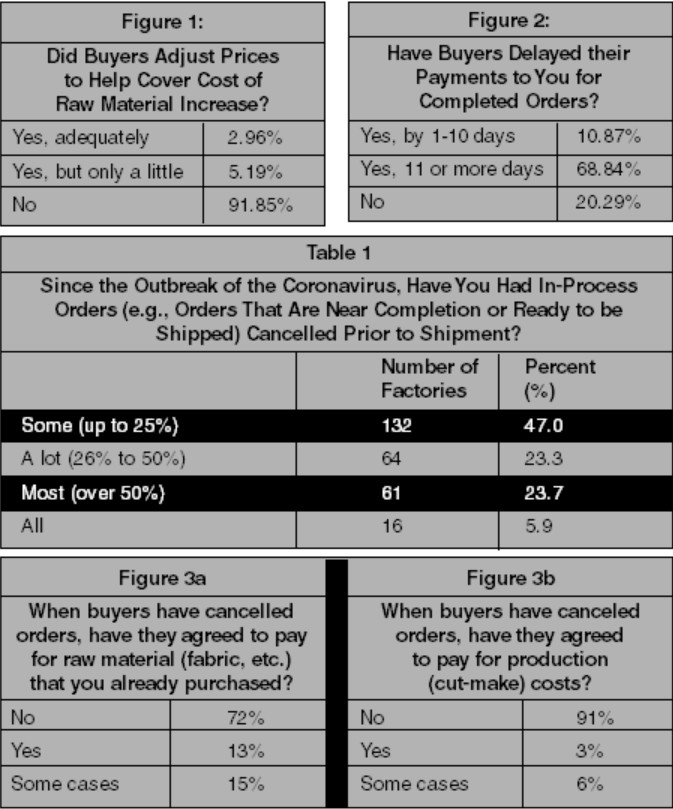

According to our survey findings, 93% of Bangladesh suppliers reported delays in raw material shipments from China. Of these, 53.4% indicated that buyers subsequently penalized them for the resulting delays in their shipments. In addition to the delays in receiving raw material, 38.3% reported that the price of their raw material increased by ‘a lot,’ and 47.7% reported prices increased ‘some’ as a result of the crisis in China. When asked if buyers adjusted their prices in response to a large increase in raw material prices, 91.9% said no. [See Figure 1.]

Crisis Phase Two: Delayed Payments

As the Covid-19 pandemic began to hit the bottom line of buyers, suppliers reported increased delays in payments. Our survey confirms these reports. 10.9% of suppliers said they experienced delays of 1 to 10 days in payments, relative to contractually stipulated terms, and 68.8% said they experienced delays of more than 10 days. [See Figure 2.] Indeed, according to Mostafiz Uddin, some buyers were pushing back payments by 30 days or more.

Crisis Phase Three: Cancellation of Orders in Progress

By mid-March 2020, an even deeper crisis began to hit the industry. Buyers began to abruptly cancel (or put on hold) not only future orders, but orders already in process. Some of these orders were entirely finished and ready to be shipped, but the buyers refused to accept order shipments or honor their contractual obligations to pay for these orders. At the time of the survey, 23.4% of suppliers indicated that “a lot” of in-process orders had been canceled, 22.3% had “most” of their in-process orders canceled, and 5.9% had all of their inprocess orders canceled. [See Table 1.]

According to press reports, Primark – which last year posted operating profits of $1.07 billion – is one example of a buyer that canceled all its orders with its suppliers. This includes “orders already in production at factories” (emphasis mine).

Many buyers are evoking the force majeure clause in their contracts to justify the breaking of their binding obligation to pay for orders in production. But, for fashion law expert Alan Behr, this appears to be an unjustified use of the force majeure clause since most force majeure clauses do not specify pandemics as a reason for failure to pay. More importantly, according to Article 7.1.1 of the Vienna Convention for International Commercial Contracts, force majeure claims should apply to the party with the most relevant contractual obligation, which in this case would be the Bangladeshi factories producing items, not the buyers that have agreed to pay for them.

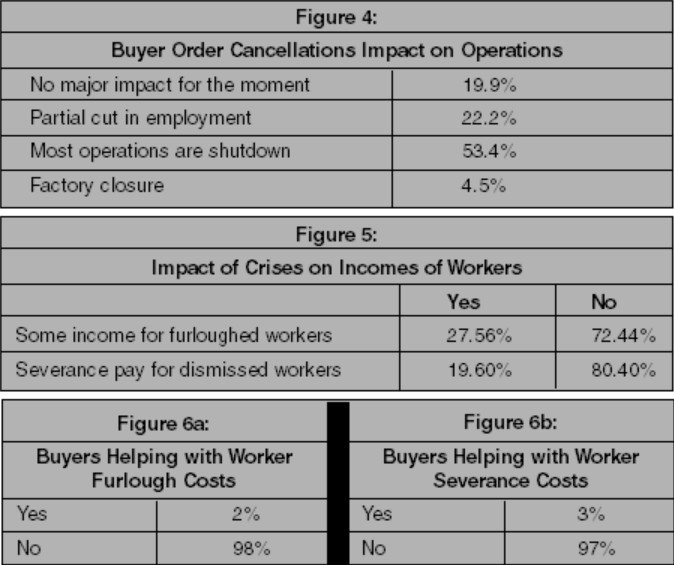

Press reports show that, as of March 22, 2020, buyers had canceled $1.44 billion worth of Bangladesh garment exports. The survey results show that in the majority of cases (72.1% of cases), when in-process orders have been canceled, buyers have refused to pay for the cost of raw material (fabric, etc.) that was already purchased by the suppliers. Buyers also refused to pay the suppliers’ cut and make production costs in 91.3% of the cases. [See Figures 3a and 3b.] The impact of these abrupt cancellations of in-process orders has been severe; 53.4% of suppliers report shutting down most of their operations and 4.5% of suppliers report having already closed their facilities. [See Figure 4.]

Impact of the Three Crises on Workers

The impact of these developments on workers has been devastating. At least 1.2 million workers had already been affected by the order cancellations. The question now is what sort of support, if any, workers can be expected to receive. For suppliers who abruptly lost buyer in-process contracts with no compensation, 72.4% said they were unable to provide their workers with some income when furloughed (sent home temporarily), and 80.4% said they were unable to provide severance pay when order cancellations resulted in worker dismissals. [See Figure 5.]

When asked if buyers agreed to assist suppliers with the cost of furloughing workers as a result of buyer in-process order cancellations, 98.1% of suppliers indicated no such support was provided. When asked if buyers agreed to assist suppliers with severance pay costs when workers were dismissed as a result of buyer in-process order cancellations, 97.3% of suppliers responded that buyers provided no such support. [See Figures 6a and 6b.]

As noted by Kalpona Akter, executive director of the Bangladesh Center for Workers Solidarity, “Garment workers live hand to mouth. If workers lose their jobs, they will lose their monthly wages that put food on the table for them and their families.” She adds, “If workers are laid off, brands should ensure immediate payments to factories so that workers receive their full legally-owed severance.” As Covid-19 starts to gain a foothold in Bangladesh, workers and their families also will be burdened with considerable health care expenses, making the payment of wages and severance all the more urgent.

Covid-19 in Bangladesh and the Government Lockdown

On March 25, 2020, the situation reached an entirely new level when the government announced a countrywide lockdown. The lockdown includes a ban on passenger travel via waterways, rail, and domestic flights. Public transportation on roads also has been suspended. However, it appears that, given the importance of garment exports to the economy, at this writing, garment export production is permitted. The challenge for those factories still receiving orders will be providing transportation to workers while fully ensuring that they are kept safe with appropriate social distancing and other measures.

Conclusions

The global apparel industry is undoubtedly in its greatest crisis in over a generation. Store closures in Europe, the United States, and beyond has shut much of the industry down. While online shopping is an option, given rising unemployment, declining incomes, and remote working, shopping for new clothes is either not an option or not a priority. Thus, the crisis of brands and retailers is real and profound. However, the way the brands and retailers are managing the crisis is envisaging damage far more dire on suppliers and their millions of workers. Decades of low prices have left many suppliers with minimal capital and now mounting debts. Years of low wages with no savings and little hope sustained government support will leave workers in dire situations. And chronic low tax revenues from buyers have left exporting country governments with weak social safety nets to assist workers in this time of crisis.

The responsible approach is for brands and retailers to find ways to access lines of credits or other forms of government support to cover their obligations to supplier factories so that they can cover their expenses and pay their workers in order to avoid sending millions of workers home with no ability to put food on the table let alone cover medical expenses.

Going forward it is necessary to re-think how the industry does business. Purchasing practices must be reformed for social and environmental sustainability. This includes stable orders, timely payments, and pricing mechanisms that cover the total cost of sustainable production, from living wages and proper benefits to tax revenues that allow governments to build proper social safety nets. And it includes allowing worker participation to be an integral part of this process through full respect for the right to form unions and bargain collectively.