Zane Berzina

Goldsmiths College, University of London

The potential of the future for both science and design lies in a multidisciplinary approach. Disciplines are merging, boundaries are melting and “many […] technologies are not significant when looked at in isolation, but become of critical importance when coupled with other technologies.”

Introduction

This paper offers a condensed case study of a cross-disciplinary practice led Ph.D. research “Skin Stories : Charting and Mapping the Skin” which dealt with issues across the fields of design, art, textiles technology, electronics, biology, material science and psychology in an attempt to bridge the gap between aesthetics and technology. The artistic investigation examines skin as a naturally intelligent material on the premise that it can serve both as model and metaphor for creating innovative textile membranes, which look, behave or feel like a skin. Attention is focussed on the living skin “technology”, meaning its complex working mechanisms, and how these have been translated into a textiles vocabulary following the principles of biomimetic design. The paper examines a range of smart textile concepts for both the body and its various environments developed during this research project at the London College of Fashion, University of the Arts London (2000-2004).

The paper also addresses the current textile practice and research of the author which deals with issues surrounding human sensory perceptions (touch, smell, vision, hearing) and how our sensory experiences could be enhanced using smart design concepts. It has been proven that the environment has a huge impact on peoples’ behaviour, relationships, their physical and psychological wellbeing. The author is particularly interested in the emerging scientific notion – called “sensism” – of how “subtle multisensory cues drive our perceptions, behaviour, decisions and performance.”

For example, visual images and olfactory messages influence peoples’ minds in subliminal, emotional, subconscious ways and this can be successfully used in new polysensual and therapeutic design concepts that support peoples‘ wellbeing and interactions. Addressing this context the practice led inquiry reflects on current developments within materials research and technologies by considering their possible applications within design and arts to create new sensory environments that respond to peoples‘ needs and improve the quality of our lives. Identification is made of areas of applications where responsive, active and interactive textiles systems, adapted from the biological skin workings, could prove to be of some value. Albeit the preoccupation with the technological and biomedical aspects the author also was constantly interested in the poetic and social context of the epidermis, as from a designer‘s point of view it was important to capture the multi-layered nature of the skin.

On this project the author collaborated closely with the Institute for Biology and Zoology, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, with TITV – Textile Research Institute Thuringia-Vogtland in Germany, the Institute of Textile Technology and Process Engineering Denkendorf in Germany and the Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Polymer Research in Berlin.

Re-working the Skin through the Medium of Textiles

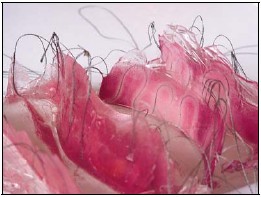

The research, discussed in this paper, explores body and skin tissue in terms of biological chain reactions and mechanisms aiming to translate the unique skin “technology” into the textiles vocabulary. The intent was to examine the “living fabric” from a textile designer‘s perspective, employing biomimetic design methods, in order to use it as a model and metaphor for the development of new textile systems. Being our largest organ, skin also represents personal and social identity. In fact, this sheltering envelope may be viewed as the fabric of the body (figs. 1a, 1b, 1c). The skin, being an interface between the body and its environment, is a major site for intercommunication between the two. “Here […] a number of different body systems come together in synergy to fulfil general overall functions beyond their individual specialized functions”.

This complex “technology”, incorporated into the sensuous fabric of skin provides us with an impressive example of an intelligent approach to problem solving by working interdisciplinarily. At various levels, there are many lessons we can learn from the skin in order to engineer and design new surfaces and products.

The principal objective of the research was to develop and test functional, active and interactive textiles that enable individuals to experience a responsive and polysensual environment addressing the biological senses e.g. vision, touch, smell. It was anticipated that the new textile systems should respond to peoples’ needs, enable them to enhance their sense of wellbeing and offer them the possibility of interacting with their surroundings.

Selected properties of the skin were translated into a textiles vocabulary by identifying a range of textile-related technologies. In order to do this, the functions of human skin tissue were examined from the perspective of a textile designer to develop different responsive and active concepts. These included :

- exploration of the potential of textiles as latent heating systems to control room temperature (the analogy of skin being a thermo-regulator);

- examination of the thermochromic properties of textiles as indicators of fluctuating conditions in the interior (the analogy used is that of human skin reactions to physical and psychological stimuli – skin as sensor and biochemical mechanism);

- investigation of the interactive and decorative potential of thermochromic and touch-sensitive surfaces to exploit transient skin images and patterns (the analogy used is skin as a sensor). and

- exploration of the olfactory and filtering potential of textiles as deodorising, antimicrobial and curative surfaces (analogy – skin as immunological surveillance and biochemical mechanism).

Subsequently the entire research project was divided into three main themes :

- Memory & Identity (where skin was looked at as a complex genetic and social display)

- Protection & Comfort (where skin was examined as barrier and exchange mechanism for comfort)

- Sensorium & Communicator (where skin was investigated as responsive, interactive and multi-functional membrane).

Our skin‘s naturally interactive and multi-functional “technology” has informed this biomimetic design research by suggesting means by which the initial biological information might best be interpreted. For example, sensory information from the outer world gathered by the skin is sent to the brain in the form of electric impulses. This biological mechanism suggested the use of electric current as the main stimulus for certain processes to take place and to corroborate the interactivity of the new textile membranes. Therefore electronic systems were incorporated in some of the work as discussed later.

Sensory Textile Wall

Figs : 2a, 2b. “Touch Me Wallpaper” at the exhibition “Touch Me,” Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 2005. Visitors interacting with the responsive textile wall. Photo © Zane Berzina.

“Touch Me Wallpaper” (figs. 2a, 2b) is an interactive sensory-appeal wall-covering prototype where touch triggers visual responses. The wallpaper responds to human heat by changing colour – people can interact with it by leaving their temporary body prints on the surface treated with thermochromic inks. The polysensual wallpaper concept carries the idea of skin as a sensor and receptor, display and communicator. Some versions of the “Touch Me Wallpaper” release various aromatherapeutic fragrances, when triggered by hand. In this case the olfactory and filtering potential of textiles as deodorising, anti-microbial and curative systems is explored referring to skin as an immunological surveillance and biochemical mechanism.

Microencapsulation technology, used in this work, permits the incorporation of aromatic oils into textile substrates to enhance the environment by releasing scent. The olfaction can, to various degrees, help people to reduce stress, enhance relationships and help heal their bodies and minds. The concept of integrating scents in buildings is not new – for centuries Arabs were using fragrances as a component in the mortar for certain mosques.

The response from the audience to this work was particularly positive. People liked to interact with the textile wall by experiencing the scent, leaving their handprints and observing how they slowly disappear from the surface like shadows. The idea of touching things that we usually do not touch and having unexpected sensory experiences was found to be interesting and capable of adding an extra value to our everyday surroundings.

The concept of an interactive sensory-appeal wall covering could be used in many ways. For example, for health care applications and as a learning environment for children. Apart from the purposes of aromatheraphy, the integration of scented messages into environments and objects would be beneficial to blind people as their olfactory sense can be activated more to get oriented in space. An opposite concept of smell absorbing textile technologies for environments could also be used by incorporating smell/malodour absorbents or technologies that absorb certain harmful substances (eg nicotine) in our environments.

In the author‘s opinion, which is based on peoples’ response to the work, ‘touch sensitive‘ walls and olfactory textiles have a potential for future design applications all of which are becoming increasingly senses orientated. Future and research conscious companies, including Outlast Technologies, are seeing a large market segment for products that offer haptic and other sensory experiences.

Drawings with Electricity

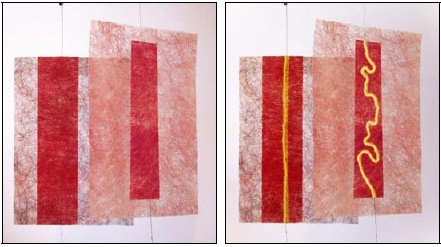

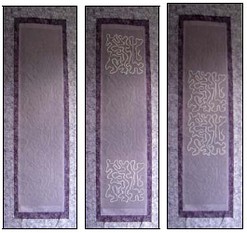

Figs : 3a, 3b. “Sensory Screen,” 2003. Before and after the colour change effect takes place. Photo © Zane Berzina

During the research project the author became interested in the idea of “drawing“ with electricity. Employing the properties of an electric current, semi-conductive treads that react to electric current by heating and thermochromatic inks which change colour in response to heat, temporary linear patterns were created. This refers to the skin analogy and the nervous system at work – the neurons sending information collected from the outside world to the brain through electric impulses.

These experiments resulted in a prototype called “Sensory Screen” (figs. 3a, 3b) where the colour change process is controlled by opening and closing the circuit using a remote control. When the electric circuit is open, the space divider reveals latent linear patterns in reaction to the heat created by the electric current flow through the conductive thread integrated into the base material. A similar principle is employed for the creation of the artwork “System I” (figs. 4a, 4b) where instead of conductive threads electrically heated conductive base fabrics are used. There is a huge potential for extending this idea into more complex patterns, drawings, maps or intelligent signage that could in the future be invisibly and discreetly incorporated into walls, carpets or clothing and activated when needed. Currently analogue systems only are used to ‘animate’ the cloths but in order to achieve more sophisticated displays digital systems could be used. The integration of digital technologies would establish the ‘skin – brain’ analogy where the computer is the ‘brain’ and cloth is the ‘skin’ – the interface between the viewer and the computer.

Another work is from a series called “Skin Architecture” (fig. 5) and it is based around the inspirations derived from magnified skin structures, its constructions and technology. The work refers to the interactive mechanisms of our body, including our sensory and vascular systems, sweat glands, hair and skin cells that all work together in harmony to form or support the functions, processes and the physicality of the skin tissue. For the production of work silicone was used as a sculptural material, finding that its flesh-like quality works as a natural allusion to the body and skin. This has been combined with a conductive stainless steal filament yarn, embedded into silicone rubber coloured with thermochromic inks that performs a slow and meditative colour play when the voltage is charged through the entire networked structure creating electric heat. Some pieces from these series also release aroma when triggered by an electric current. Due to the incorporated colour change technology heat is drawing sophisticated patterns on the fleshy 3D structures. The slow, radiant colour change plays offer a calming experience that is almost a meditative one when the viewer is taking the time to engage in the process.

The sculpturaly elaborated pieces of the “Skin Architecture” aim to offer unusual sensory experiences that involve sight, smell and touch. They can be used as precious objects or decorative tiles applied in a series or as one-off pieces to enhance peoples sensory environments by releasing aromatherapeutic fragrances, performing soothing colourplays and intimately responding to touch helping to reduce stress. Such multi-sensorial systems would prove useful for hospitals, health resorts and physicians waiting rooms and could offer a unique experience, which enhances people‘s emotional and physical wellbeing in calming and therapeutic ways, and also provide a personalised environment.

Conclusion

Through the research and practical investigations from a designer‘s point of view the author has discovered that the properties and mechanisms, incorporated in human skin, can contribute to and be a catalyst for the development of new approaches to smart textile design systems. As a result responsive, active and interactive textile design solutions have been developed at a prototype stage that embody selected skin-like aspects such as its aesthetic, sensory, somatic and tactile qualities for possible application in body-related concepts and living environments. These combine technologies currently commercially available with the author‘s expertise as a textiles designer. By enhancing our physical and psychological wellbeing and improving our sensory environments, these textiles could encourage people to explore their senses in novel ways. However, still a lot of further research and testing is needed in order to bring these ideas into real living environments. All this work would not have been possible without the collaborative assistance from the technologists and scientists I was working together with on this project. By establishing a common language we managed together to achieve interesting outcomes.

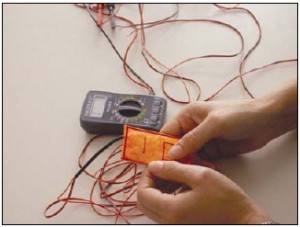

Fig. 6 : Flexible textile switch, developed in collaboration with TITV, Germany, 2005. Photo © Zane Berzina

Fig. 7 : Testing of optimised conductive yarns in a non-finished colourchange textile system. Collaboration with TITV, Germany. 2006.

Fig. 8 : Application of conductive yarns using CAD stitching processes. Collaboration with TITV, Germany, 2006.

Figs 9a, 9b, 9c : Electronic textile prototype with integrated colour change modules using computer aided stitching. Each module can be addressed and activated individually. Images are showing various stages of colour change effects. (TITV, 2006)

The “Sensory Screen” concept discussed in this paper is now being developed further by the author in close collaboration with TITV – Textile Research Institute Thuringia-Vogtland in Germany. Their scientific and technical assistance as well as access to specialised industrial equipment is crucial for the realisation of the prototypes into real products. To date a flexible user-friendly textile switch (fig. 6) has been developed to replace the hard remote control which was used previously to switch on or off the electronic textile systems. A series of tests have been conducted in order to optimise the specialised semi-conductive yarns for specific end applications (fig. 7). Intense work has been done to industrialise the conductive yarn application techniques on various textile substrates using computer aided stitching machines (fig. 8). The initially very fragile electronic textile systems have now been improved and much more sophisticated active textile displays have been made which can be reproduced industrially (figs. 9a, 9b, 9c). All this allows the author to continue the investigations on a larger scale, offering a wider range of design possibilities in terms of the complexity and variety of latent patterns, colour combinations and rhythms of colour plays. (Courtesy : The Textile Society of America)